By Bryna Godar

When Chisom Esele walks around the University of Minnesota campus at night, people sometimes get nervous, walk faster or cross the street when they see him coming.

“I feel like when you're black and you’re walking on the street at night, you're kind of viewed [in a certain way],” the electrical engineering junior said. “I kind of understand, but at the end of the day, when this kind of stuff happens to me … it affects the way I feel.”

With the recent string of crime alerts emailed to University students, faculty and staff, the black community has an additional safety concern: racial profiling.

All but two of the 19 crimes in alerts sent this semester have described one or more young, black males as suspects. The other two didn’t include race descriptions.

“The problem is that it’s not descriptive enough to say who they’re actually looking for, because a black male in their 20s is me, and I’m a professional staff member here,” said Black Faculty and Staff Association logistics and technology coordinator Delonte LeFlore.

Black faculty, staff and students across the University are working with police, administrators and the campus community to address the growing safety issue. They say they are worried about racial profiling by police, racial fear in the community and the potential for the situation to escalate into racially based violence.

“Our big question is, how do you keep this campus safe from crime while also keeping people of color, particularly ... black men, safe from racial profiling,” said BFSA President Alysia Lajune.

Calling for ‘urgent’ University response

A month after meeting with University police Chief Greg Hestness to discuss the impact of the crime alerts and steps to address racial profiling, members of the University’s black community said they haven't seen a change.

Six groups sent a letter to President Eric Kaler and University Services Vice President Pam Wheelock on Friday, asking University police to work with the groups, and provided a list of recommendations to address racial profiling.

The primary recommendations involve posting the University police department’s policy on racial or bias-based profiling on its website, sending a University-wide email detailing the policy and including the policy in crime alerts.

After receiving the letter Friday, University Services spokesman Tim Busse said those requests will be in place by the end of the day Monday.

The BFSA, the Black Graduate and Professional Students Association, the Black Men’s Forum, the Black Student Union, the African American & African Studies department and Huntley House for African American Men all signed the letter.

University police policy defines racial or bias profiling as “any action initiated by law enforcement that relies on the race, ethnicity or national origin of an individual rather than the behavior of that individual.”

“I think our University officers do a very good job fighting against the notion of racial profiling,” Busse said. “Their policy is to profile behavior and not race.”

University police began logging extra overtime in October in response to the recent crimes around campus, according to an email Wheelock sent to the University community.

Addressing the Faculty Senate on Thursday, Kaler said the “aggressive law enforcement” is paying off but that the current strategy can raise concerns about racial profiling.

“I am confident that the law enforcement strategy we’re pursuing is the right one to curb crime,” he said at the meeting. “But it will take time to see sustained results, and we need to remain vigilant to not profile based on race.”

But the University’s black community is concerned about the increased police presence.

BFSA treasurer Bereket Worku said police have pulled over both he and LeFlore in the area for “no reason.”

Lajune said she always checks her speedometer when she sees a police car in order to “not give a reason to be pulled over.”

Black Men’s Forum President Ian Taylor Jr. said a petition to increase police presence bothers him “because usually when there’s an increase in police presence, it’s not very good for black people in general.”

‘Vague’ suspect descriptions

Black students, faculty and staff agreed that the string of suspect descriptions have created an unsafe environment for them.

“What it’s doing to us is it’s painting us as threats to everyone,” said Black Men’s Forum Vice President Abdel-Kader Toovi. “They’re not separating the black men on campus from these out-of-campus people coming in.”

The letter sent Friday recommends removing race descriptions from crime alerts, because the Jeanne Clery Act, which requires the University to send crime alerts, doesn’t mandate them.

“What we’re saying is UMPD needs to know the full description, but the University community’s job is not to be volunteer police officers and help you catch criminals,” Lajune said. “So how important is it that we have these descriptions?”

Mechanical engineering senior Joseph Lee said he thinks the descriptions aid in identifying suspects.

“Without a description, you lose the power of the public,” he said. “I don’t think racial profiling is perpetrated by the description but by people’s interpretation of that.”

Busse said the alerts aim to help individuals identify suspects and either bring that information to police or use it to stay safe.

“We’re trying to give enough information that if someone saw that person walking down the street, they could recognize them and react appropriately,” he said.

For now, Busse said, he thinks the alerts should still include suspect descriptions.

But many are concerned the descriptions are too vague.

“Every time I see a description, I can think of 10 people that fit that description,” Worku said.

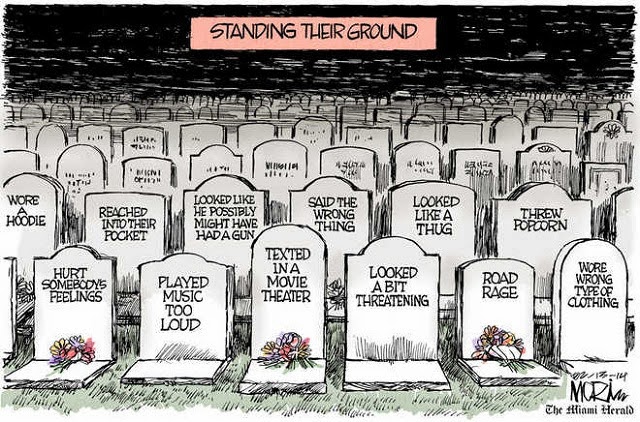

Particularly in light of discussions of the right to conceal and carry, some worry the campus climate could become hostile.

“What many in the black community fear is this could spiral out of control,” Taylor said. “We want to stop it before it gets to that point.”

Moving forward

As the University heads into spring semester, these groups are planning to work with police and administration on events and education to address the issue on campus and throughout the Twin Cities.

“Racial profiling is not just something that police officers do; it’s something that everybody does,” LeFlore said.

Even before the crime alerts, black men have had to move carefully, Taylor said.

“There definitely is this reaction: You don’t want people to feel threatened by you,” Taylor said. “As black men, we don’t want to have to worry about that ... but it’s just the reality.”

Sometimes that means smiling more or crossing to the other side of the street if walking behind somebody, he said.

“They feel like they have to adjust themselves, and that’s disturbing to me as well,” Taylor said. “It’s reminiscent of Jim Crow [laws] ... when there’s social standards you must operate by.”

Lajune said the groups want to open discussion, allowing people to “step up to the mic” and share their stories.

BSU President Amber Jones said the administration should have the same urgency regarding concerns of racial profiling that it’s had addressing campus safety.

“This has to be a part of the conversation,” she said.

The letter sent Friday also recommended that UMPD work on relationship-building activities with black students and that administrators engage in a listening session.

The groups hope to engage the Minneapolis and St. Paul police departments as well, because they handle most off-campus crime.

“This is the start of the discussion of how we can attack it as a whole in all three areas,” LeFlore said.

Busse said University officials, including police Chief Hestness and University Services Vice President Wheelock will discuss the other recommendations.

“I'm disturbed with the climate on campus,” Taylor said. “I think there’s a lot of potential in this moment to increase the way we can make our community safer.”