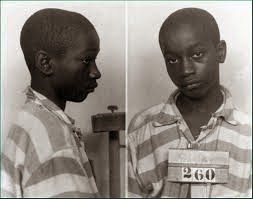

George Junius Stinney Jr., the 14-year-old Black boy who died as the youngest person ever executed in the United States in the 20th century, would have been 83-years-old this Sunday. Instead, his birthday will serve as a haunting reminder of why the death penalty needs to be abolished. When two White girls, 11-year-old Betty June Binnicker and 8-year-old Mary Emma Thames, went missing in Alcolu, S.C., on March 22, 1944, after riding in to town on their bicycles, Stinney was arrested the following day for allegedly murdering them.

Without his parents, Stinney was interrogated by several White officers for hours. A deputy eventually emerged announcing that Stinney had confessed to the girls’ murders. The young boy allegedly told the deputies that he wanted to have sex with the 11-year-old girl, but had to kill the younger one to do it. When the 8-year-old supposedly refused to leave, he allegedly killed both of them because they refused his sexual advances.

To coerce his confession, deputies reportedly offered the child an ice cream cone. There is no record of a confession. No physical evidence that he committed the crime exists. His trial — if you want to call it that — lasted less than two hours. No witnesses were called. No defense evidence was presented. And the all-White jury deliberated for all of 10 minutes before sentencing him to death.

On June 16, 1944, his frail, 5-foot-1, 95-pound body was strapped in to an electric chair at a state correctional facility in Columbia, S.C. Dictionaries had to be stacked on the seat of the chair so that he could properly sit in the seat. But even that didn’t help. When the first jolts of electricity hit him, the head mask reportedly slipped off, revealing the agony on his face and the tears streaming down his cheeks. Only after several more jolts of electricity did the boy die.

George Junius Stinney Jr. was, at age 14, the youngest person executed in the United States in the 20th century (1944) The boy was very small for his age (5'1) so small, they had to stack books on the electric chair. http://tinyurl.com/mpt2jgj

This clip is from the 1991 movie "Carolina Skeletons" which is based on that event. (I have no ownership or copyrights concerning this film)

Because there is literally NO EVIDENCE AGAINST HIM (accused of murdering two white girls) ...the question of Stinney's guilt and the judicial process leading to his execution remain controversial (ie. there's a strong possibility they executed an INNOCENT person).

George Stinney, Jr. and Sister (left)

Chip Finney, 3rd Cir. (SC) Solicitor (right)

"Nothing Good": Jim Crow-Era South Carolina and the George Stinney, Jr. Case

In the past, the LHB has reported on Jim-Crow-era cold cases and efforts in Alabama and other places to rectify injustices from the era of segregation. Add the George J. Stinney, Jr. case to the list. In 1944, the state of South Carolina executed George J. Stinney, Jr. a fourteen-year-old black boy, for the murder of two white girls, ages seven and eleven. A jury had convicted Stinney after a short trial in Clarenden County (of Brown v. Board fame) that turned on the boy's reputed confession. A child psychologist now calls that confession "compliant, coerced, and false."

Mere months after the crime, South Carolina electrocuted Stinney, making the fourteen-year-old the youngest person executed in the twentieth century United States. Seventy years later, Stinney's family is seeking a new trial or a voided verdict to clear his name. The history of the state of South Carolina during the era of segregation and how prevailing social attitudes may have influenced the central actors in the case--including Stinney, prosecutors, and police officers--are vital to the legal drama now unfolding in the courtroom. One of Stinney's sisters succinctly captured a slice of the black experience when asked "what she recalled of her life" then. Her response: "nothing good." The Stinney family left the Deep South for Newark after her brother's death "shattered her parents." The effort of the Stinney family to clear George, Jr.'s name is opposed by the state, which is represented by Chip Finney, pictured above right, the Third Circuit Solicitor; the state argues that the evidence is too speculative to unsettle the verdict. In addition, the niece of one of the victims argues that the boy's confession and conviction are valid under the laws of 1944.

Coverage of the Stinney saga can be found in The State (SC) and in the N.Y. Times. The case also has spawned an award-winning, true-crime novel, Carolina Skeletons, by David Stout, formerly of the N.Y. Times. For a thoughtful, multi-part retrospective about his discovery of Stinney and the local context in which the crime, investigation, and execution occurred, see Stout's discussions here, here, here, and here. Here is an excerpt from Part 1 of the series:

As a journalist, I’d always been drawn to criminal justice issues, especially capital punishment. ... I’ve always favored the death penalty for truly horrible crimes. But should the state put a killer to death if he isn’t old enough to live on his own, or vote, or buy a beer? ...

Quickly, probably too quickly, I formed an opinion. Since George Stinney was black, and the little girls were white, he was doomed from the start. He was lucky to have died from the electric current rather than strangling at the end of a rope thrown over a tree limb by a lynch mob in the bigoted, rebel-haunted South Carolina of 1944.

Over 67 years after 14-year-old George Junius Stinney Jr. was put to death by the state of South Carolina, he may soon be cleared of the crime that people familiar with the case say he never could have committed.

A lawyer and an activist both told Raw Story recently that new evidence will show that the black boy could not have possibly murdered two white girls, 11-year-old Betty June Binnicker and seven-year-old Mary Emma Thames.

Stinney, the youngest person to receive the death penalty in the last 100 years, was executed on June 16, 1944. At five feet one inch and only 95 pounds, the straps of the electric chair did not fit the boy. His feet could not touch the floor. As he was hit with the first 2,400-volt surge of electricity, the mask covering his face slipped off, “revealing his wide-open, tearful eyes and saliva coming from his mouth,” according to author Joy James .

After two more jolts of electricity, the boy was dead.

Less than three months earlier, Stinney, who had no previous history of violence, had been accused of the crime after he admitted speaking to the girls when they stopped by a field in Alcolu where he was grazing his cow to ask where they could find maypops, a type of flower. Authorities alleged Stinney had used a railroad spike to shatter both of the girls’ heads. The boy was taken into a room with several white officers and within an hour, they said he had confessed. Because there were no Miranda rights in 1944, Stinney was questioned without a lawyer and his parents were not allowed into the room.

No written confession exists, only a few handwritten notes a deputy who was present during the interrogation. They claimed that Stinney had said he killed Mary Emma because he wanted to have sex with Betty June. When Betty June resisted his advances, authorities said, he murdered her too.

Reports said that the officers had offered the boy ice cream for confessing to the crimes.

A mob of about 40 angry white men showed up at the jail, demanding to lynch Stinney, but he had already been moved about 50 miles away to Columbia. Even though Stinney’s father had helped search for the girls when they went missing, he was fired and forced to leave the home provided by Alderman’s Lumber Mill where he worked.

The court appointed 31-year-old Charles Plowden, a tax commissioner, to defend Stinney.

“Plowden had political aspirations, and the trial was a high-wire act for him,” author Mark R. Jones wrote . “His dilemma was how to provide enough defense so that he could not be accused of incompetence, but not be so passionate that he would anger the local whites who may one day vote for him.”

Plowden did not cross-examine any of the prosecution’s witnesses, nor did he call any witnesses for the defense. His entire argument was that Stinney had been too young to be held responsible for the crime, but under South Carolina law at that time, 14 was considered to be age of criminal liability.

The trial was over two hours after it began. A jury of twelve white men deliberated for 10 minutes before convicting Stinney. Plowden later told the judge that there was nothing to appeal, and the Stinney family could not afford to continue the case. A one-sentence notice of appeal would have automatically stayed the case for a year.

While Plowden was preparing a run for state House that Spring, he was not the only one for which the trial held political implications. As elected officials, Sheriff Gamble, Judge Phillip Henry Stoll, Gov. Olin Dewitt Talmudge Johnston, Coroner Charles Moses Thigpen and State Sen. John Grier Binkins, who were all involved in the case, were also beholden to white voters.

State Sen. Binkins assisted the prosecution and Gov. Johnston could have commuted the sentence. Coroner Thigpen had testified that while there was no evidence of rape, he could not rule it out, an inflammatory statement that would have normally been subjected to cross-examination.

Only 83 days after first being accused of the crime, Stinney was put to death.

Attorney Steve McKenzie told Raw Story that he has no doubt this case was an injustice.

“You can’t try a [general session-level] case in two hours,” McKenzie explained. Plowden “would have had an ethical obligation to appeal the case. He would have had an ethical obligation, also, to cross-examine the witnesses but he didn’t do either one of those.”

“The defense attorney obviously didn’t even know what he was — he wasn’t a criminal lawyer, he was just someone that was appointed. He argued that you couldn’t execute George Stinney because he was 14. Well, the age was 14 for an adult at the time. So, he argued actually the wrong argument in his closing statement.”

McKenzie said that the lack of preserved evidence made clearing Stinney’s name difficult, but he hoped that the affidavits of three new witnesses, one of which could provide an alibi, would be enough to re-open the case.

“If we can get the case re-opened, we can go to the judge and say, ‘There wasn’t any reason to convict this child. There was no evidence to present to the jury. There was no transcript. This case needs to be re-opened. This is an injustice that needs to be righted.’”

“I’m pretty optimistic that if we can get the witnesses we need to come forward, we will be successful in court,” he added. “We hopefully have a witness that’s going to say — that’s non-family, non-relative witness — who is going to be able to tie all this in and say that they were basically an alibi witness. They were there with Mr. Stinney and this did not occur.”

Activist George Frierson, who is also from Alcolu, said that he had come across the case about five and a half years ago while doing black historical research and has been fascinated ever since.

“The fact that he was 14 just astounds me,” Frierson told Raw Story. “I’m a military veteran and I always tell people that the two things that we protect is our elders and our children. And to have this happen to a 14-year-old child, it was appalling.”

“I was born in Alcolu, where he was living at the time of this incident, and it always has been talked about in the community. In fact, there has been a person that has been named as being the culprit, who is now deceased. And it was said by the family that there was a deathbed confession.”

He added that the rumored culprit had come from a well-known, prominent white family. Another member of that same family had served on the coroner’s inquest jury which recommend that Stinney be prosecuted.

Frierson hopes that clearing Stinney’s name would make people think twice in other death penalty cases like that of Troy Davis, who was recently executed by the state of Georgia. Since his conviction, seven of the nine people who testified against him had recanted or changed their testimonies.

“I have a problem with the death penalty because it is irreversible,” Frierson said. “You find out later that someone actually was innocent then you go and say we’re going to settle a wrongful death lawsuit. What does that do for the victim? Nothing. It doesn’t do anything for them.”

“I think it will make people look a little more closely. Just like the seven people that recanted in the Troy Davis case… After seven people recanted a story out of nine, if that’s not reasonable doubt, I don’t know what is. And yet, the state of Georgia decided to go through with the execution.”

If Stinney’s name is cleared, it won’t be the first time the state of South Carolina has learned that the it put the wrong person to death.

In 2009, the South Carolina Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services unanimously pardoned Thomas Griffin and Meeks Griffin for the 1913 murder of John Q. Lewis, a former Confederate Army veteran.

“It’s good for the community,” radio show host Tom Joyner, who had two great uncles that were also executed for the crime, told CNN. “It’s good for the nation. Anytime that you can repair racism in this country is a step forward.”

Watch this video from CNN’s Newsroom, broadcast Sept. 30, 2011.

LINK TO SEVERAL VIDEOS ON CASE:

George Stinney Case Hearing: More Parts on YouTube

.jpeg)